The truths are not screaming. You must listen carefully and you must be lucky.

Enrique Martinez

Recently, I found my way to a cave retreat in the Cochise Stronghold, a jewel of a small, granite-rimmed basin within the Dragoon Mountains of Arizona. Just those names coming off one’s tongue conjure up a certain power of place. That power is palpable everywhere around the Stronghold. The area features hundreds of “fracture caves,” and thus the ability to, long ago, help First Americans hide from and fight the cavalry, and the ability now for the Dharma Treasure Retreat Center to send visitors off into caves for retreats of various lengths. Here in the USA, there are yogis meditating in caves for months at a time. Echoing the First Americans, they’re hard to find and they like it that way. Dharma Treasure even boasts a Thai Forest monk who caves it 6 days a week and comes down for alms on Saturdays.

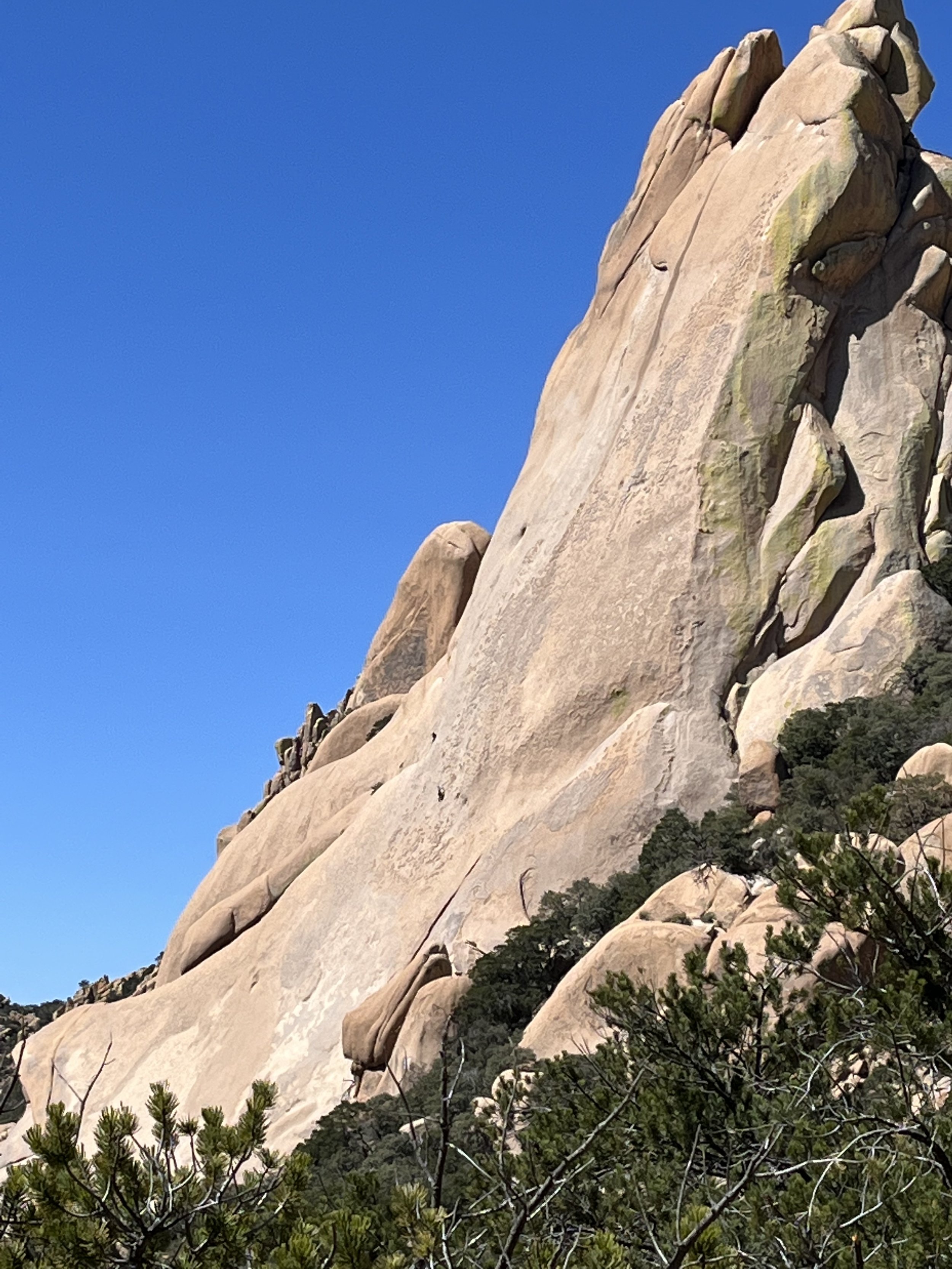

Those of you who hike in the desert have likely felt scraped clean by the cloudless sky juxtaposed against towering rock slabs and elephantine boulders.

At the beginning of my solo trip, with no distractions and a sudden be-wildering silence when my guide left me, I soon found myself speaking aloud for company. It seemed a very human gesture, like raising my puny fist to the sky and declaring, “Hey, Nobody! I’m here!”

Not for long answered the rock.

The desert’s stillness is overwhelming to us moderns, even though we must know—in the abstract at least—this auditory landscape as our ancestral base. Although some of us beg for more stillness and quiet in our lives through meditation or prayer, the Dragoon version felt too enormous to rest easy. At least initially. I think of the poet, Marie Howe, who said in a recent interview with Krista Tippet that it “hurts to be present.” Present-ness is my personal mantra these days, but this present-ness was impersonal, massively impersonal.

The actual climbing into the rock, into a cave for shelter, cooking, and sleep stunned me further. I felt I’d entered a mouth that swallowed not only the very last of my words, but also my thoughts, even the few needed to start a twig fire, blow up my pad, and unpack my sleeping bag. I managed, but the cave made no promises to protect me from scorpions, rattlesnakes, and cougars. All that remained of me in this environment was attention, wide-eyed attention for most of the night.

Our lives are so often “virtual,” translating the intimacy of direct experience into the metaphor of language, braving the world with shields of ideas. “As soon as we are spinning a narrative about something, we are no longer seeing it for what it is. We are not capable of doing both things at the same time,” says writer Jeannine Ouellette. That’s a bold statement that never felt truer to me than in the Dragoons. My thoughts had no audience—not even me after a time. I felt continually forced into the great question of Zen, “What is this?” When you ask that of a desert, emptiness responds.

These rocks rebuffed any attempt to wrap them in narrative. So did the century plants, the shin daggers, the manzanita, and the cat claw shrubs. How did they get here? How do they survive here? The story of how these rocks came to be, and what they represent in terms of geologic time—no less galactic time—is beyond anything I could conceptualize.

During the coldest hours before dawn, it occurred to me I had a lot of ancestors to thank over the millennia who managed to rise above survival to create civilization. When it takes so much time to simply fetch water, gather sticks and nurse a fire for a hot drink, that lighter in my palm—representing the evolution of comfort—became an astonishing accomplishment.

Over these few days I spent in the desert, the aperture of the question—what is this—opened up. My curiosity simultaneously chased after it and hid from it, reminding me of the definition of awe: reverential respect mixed with wonder and fear. It did hurt to be present against that edgeless frontier of amnesic blue, scorching sun, and rocks that literally scraped the skin off me.

Then again, I felt so alive. Despite the hundreds of hikes, the dozens of nights camping, and many trips to the deserts in Utah, I had never felt quite so disturbed—in all the best ways of waking up—by nature as I did in the Dragoons.

I came back a day early to the Stronghold. When I saw the buildings, the flock of chickens scratching in the yard, a few cars parked in the shade of trees, the laundry line with the semaphores of personhood, the things I recognized as human comfort, I both missed and felt relieved at what I’d left. I did not wholly succeed in sustained attention to that unstoried silence in my cave for long, but I’m mighty intrigued and curious now to return and meet it again for a longer time.

Back in the Stronghold, I found a rock and couldn’t help myself with a bit of graffiti. I had to give it some words:

Later, the resident monk suggested I write on the other side:

When Henrik, the resident cave yogi, left for the mountains the next day, he managed to get cell service from a perch up high and sent me a text that completed my learning: “When I’m in the mountains, I am the mountain.”